Researchers from the University of Cincinnati (UC) College of Medicine have developed an antibody to prevent the effects of cocaine from reaching the brain, which could be a groundbreaking innovation for those seeking cocaine addiction treatment.

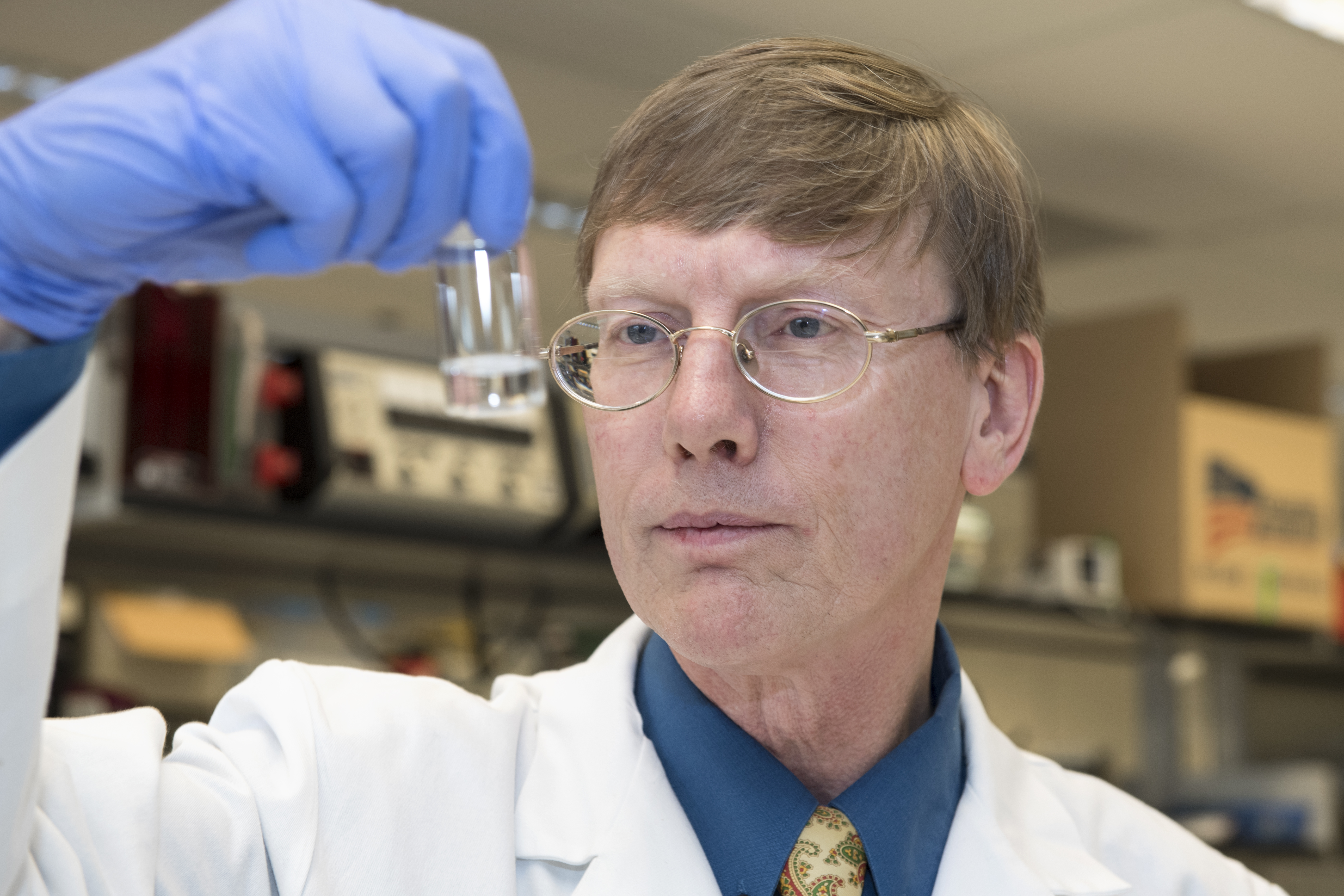

Andrew Norman, Ph.D., professor of pharmacology in the UC College of Medicine, directed the team that created the anti-cocaine immunotherapy, which has been successfully tested in animal models. The drug consists of a human monoclonal antibody — an antibody made in a lab to mimic the cells that are produced by a person’s immune system. When the new antibody is injected and comes in contact with the bloodstream, it attaches to the cocaine molecules present in the system and prevents it from entering the brain.

“Monoclonal antibodies are typically generated in mice, but we had access to a new technology, which used transgenic mice,” Norman said. “So, the antibody genes of a mouse were deleted and substituted with human counterparts. These transgenic mice were able to produce all human antibodies but using standard monoclonal antibody techniques, we were able to produce human antibodies from mice.”

Vaccines designed to produce an immune response against cocaine were given to the mice. The researchers were then able to isolate the human antibodies with specific properties, such as high affinity and selectivity for cocaine, from the metabolites of cocaine, cutting its effects.

However, the humanized anti-cocaine monoclonal antibody was not developed to cure cocaine addiction. “The antibody will not cross the blood-brain barrier,” Norman said. “If you believe that the effects or the mechanisms of cocaine target the brain, which is where addiction is manifested, then the antibody will have no effect on any changes that cocaine has produced in the brain.”

Instead of curing cocaine addiction, the new drug would be a tool against relapse that could aid people who are determined to stop using the drug, Norman explained. “People who are motivated to quit taking cocaine could benefit,” he said. “If you take more cocaine, you’d be able to overcome the effects of antibody, [but] we are finding that you have to give more than a threefold of cocaine to induce a relapse event.”

Thus, cocaine dependents would have to take a dose at least three times larger than they usually did in order to overpower the antibody and experience the mind-altering effects of cocaine.

“Eventually, the clinical indication will be for relapse prevention,” Norman said. “When a cocaine addict comes out of detox and rehab into the streets, the recidivism rate is very high. There’s a very high probability they’ll relapse and take cocaine again. The relapse event, when triggered by environmental cues or stress, is transient. So, if people crave and take cocaine, they will normally go on a binge. The hope is that if they do relapse, the cocaine will be neutralized by the antibody and will not get into the brain or have any effect. This would break the cycle of addiction.”

In addition to conceivably helping individuals who are seeking cocaine addiction treatment as they leave drug rehab or drug detox, the injectable antibody would have one major advantage: it is long-lasting.

“The antibody is expected to have a very long half-life in people,” Norman added. “We expect it to have a half-life of three weeks or maybe a month. So, a single dose could last a long time, and that will be a major advantage because people don’t have to take the drug on a daily basis.”

No other drug currently available in the market blocks the effects of illicit drugs in a similar manner.

The new antibody is now at… (continue reading)